The following is from NPR and I wanted to share it to make a point. Learning is becoming decentralized. Instead of going to Stanford, Stanford came to over 160,000 students worldwide and they learned about Artificial Intelligence. Really learned it in a way that allowed for knowledge and know-how to be transferred, tested and even provide feedback to the professors to improve their course.

It’s no longer a brave new world of learning. It’s just the way it is and will be.

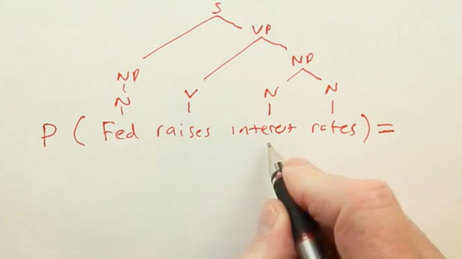

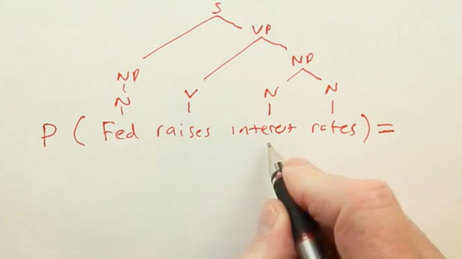

Stanford Engineering’s Online Introduction To Artificial Intelligence is made up of videos that teach lessons by drawing them out with pen and paper.

Last year, Stanford University computer science professor Sebastian Thrun — also known as the fellow who helped build Google’s self-driving car — got together with a small group of Stanford colleagues and they impulsively decided to open their classes to the world.

They would allow anyone, anywhere to attend online, take quizzes, ask questions and even get grades for free. They made the announcement with almost no fanfare by sending out a single email to a professional group.

“Within hours, we had 5,000 students signed up,” Thrun says. “That was on a Saturday morning. On Sunday night, we had 10,000 students. And Monday morning, Stanford — who we didn’t really inform — learned about this and we had a number of meetings.”

You can only imagine what those meetings must have been like, with professors telling the school they wanted to teach free, graded online classes for which students could receive a certificate of completion. And, oh by the way, tens of thousands have already signed up to participate.

For decades, technology has promised to remake education — and it may finally be about to deliver. Apple’s moving into the textbook market, startups and nonprofits are re-imaging what K-12 education could look like, and now some in Silicon Valley are eager for technology and the Internet to transform education’s more elite institutions.

Thrun’s colleague Andrew Ng taught a free, online machine learning class that ultimately attracted more than 100,000 students. When I ask Ng how Stanford’s administration reacted to their proposition, he’s silent for a second. “Oh boy,” he says, “I think there was a strong sense that we were all suddenly in a brave new world.”

Ng says there were long conversations about whether or not to give online students a certificate bearing the university’s name. But Stanford balked and ultimately the school settled on giving students a letter of accomplishment from the professors that did not mention the university’s name.

“We are still having conversations about that,” says James Plummer, dean of Stanford’s School of Engineering. “I think it will actually be a long time — maybe never — when actual Stanford degrees would be given for fully online work by anyone who wishes to register for the courses.”

‘Uncharted Territory’

Thrun’s online class on artificial intelligence or A.I., which he co-taught with Google’s Peter Norvig, eventually drew more than 160,000 students who received detailed grades and a class ranking.

“We reached many more students, Peter and I, with this one class than all other A.I. professors combined reached in the last year,” Thrun says.

Thrun believes a class that size creates a valuable credential — even if Stanford doesn’t recognize it. Students hailed from 190 different countries, including Australia, China, Ukraine and the U.S. They included high school students, women with disabilities, teachers and retirees — and they were all taking the same class Stanford students took, grades and all. But the online participants didn’t get credit.

“I think we all realized we were in uncharted territory,” Thrun says. “As we move forward, it is my real goal to invent an education platform that has high quality to it, [that] prevents cheating, that really enables students to go through it to be empowered to find better jobs.”

Widespread Impact

Stanford does award degrees for online work, but only to students who get through the admissions process and pay sometimes $40,000 or $50,000 for a master’s degree. Technology could push prices down.

Dean Plummer believes low-cost, high-quality online education will have a profound impact in high education, even at institutions as august as Stanford. He doesn’t think it will diminish demand for undergraduate degrees or Ph.D.s, but he says the impact on master’s programs could be profound.

“What it will look like in 10 years or 20 years or 30 years — your guess is as good as mine,” he says. “But I think the impact will be large and it will be widespread.”

Online education and distance learning have been going on at Stanford and other schools for years, but Plummer believes the technology has reached an inflection point.

Videos stored online let students build course work into their schedules anywhere in the world. Embedded quizzes let students monitor their own progress and give professors much richer data to improve their teaching.

Ng noticed that 5,000 students made the identical mistake in an online quiz. Within minutes, teachers were able to respond and clarify the issue that had led a large fraction of the class down a dead-end path.

Global Benefits

Daphne Koller is a computer science professor at Stanford, and a MacArthur “Genius” Fellow. She has been working for years to make online education more engaging and interactive.

“On the long term, I think the potential for this to revolutionize education is just tremendous,” Koller says. “There are millions of people around the world that have access only to the poorest quality of education or sometimes nothing at all.”

Technology could change that by making it possible to teach classes with 100,000 students as easily and as cheaply as a class with just 100. And if you look around the world, demand for education in places like South Africa is enormous.

Almost two weeks ago, at the University of Johannesburg, more than 20 people were injured and one woman was killed trying register for a limited number of openings. Thousands had camped out overnight hoping to snag one of the few available places and when the gates opened, there was a stampede.

Koller hopes that in the future, technology will help prevent these kinds of tragedies.

Trying ‘Bold New Things’

Over the past six months, Thrun has spent roughly $200,000 of his own money and lined up venture capital to create Udacity, a new online institution of higher learning independent of Stanford. “We are committed to free online education for everybody.”

Udacity is announcing two new classes on Monday. One will teach students to build their own search engine and the other how to program a self-driving car. Eventually, the founders hope to offer a full slate of classes in computer science.

Thrun says Stanford’s mission is to attract the top 1 percent of students from all over in the world and bring them to campus, but Udacity’s mission is different. He’s striving for free, quality education for all, anywhere.

Koller agrees, but she says Stanford and its professors will adapt.

“How it all is going to pan out is something that I don’t think anyone has a very clear idea of,” she says. “But what I think is clear is that this change is coming and it’s coming whether we like it or not. So I think the right strategy is to embrace that change.”

Over the years, Stanford has launched dozens of disruptive technologies into the world, but now administrators and professors seem to agree that the school may be about to disrupt itself. This semester Stanford will put 17 interactive courses online for free.

“Stanford has always been a place where we were will to try bold new things,” Plummer says. “Even if we don’t know what the consequences would be.”

I always knew that it’s all in my head, that my brain ruled and not my heart. It’s taken years of work in the Neurosciences to get to the point where they are realizing that they hardly know anything at all about the way the brain really works. John Medina, author of Brain Rules, is my favorite researcher because he’s honest about the science and at the same time very funny. If you ever get a chance to hear him speak take the time and go.

I always knew that it’s all in my head, that my brain ruled and not my heart. It’s taken years of work in the Neurosciences to get to the point where they are realizing that they hardly know anything at all about the way the brain really works. John Medina, author of Brain Rules, is my favorite researcher because he’s honest about the science and at the same time very funny. If you ever get a chance to hear him speak take the time and go.