Nobody likes change, and some people really hate it …

I suppose I should be happy. Two of my heroes, David Brooks and Thomas Friedman, both had recent articles about educational technology – MOOCs and Testing. Yet my joy has turned to consternation. Their articles have added fuel to a small but growing fire about education in general, and educational technology in particular. The theme seems to be that the machines are coming, the corporations are already here, public is morphing into private, it’s all about the money, and teachers are an endangered species.

Let’s back up a bit.

Here is what I read as a key part of David Brook’s piece The Practical University:

The best part of the rise of online education is that it forces us to ask: What is a university for? … My own stab at an answer would be that universities are places where young people acquire two sorts of knowledge, what the philosopher Michael Oakeshott called technical knowledge and practical knowledge… Practical knowledge is not about what you do, but how you do it. It is the wisdom a great chef possesses that cannot be found in recipe books. Practical knowledge is not the sort of knowledge that can be taught and memorized; it can only be imparted and absorbed. It is not reducible to rules; it only exists in practice.

The problem is that as online education becomes more pervasive, universities can no longer primarily be in the business of transmitting technical knowledge. Online offerings from distant, star professors will just be too efficient. As Ben Nelson of Minerva University points out, a school cannot charge students $40,000 and then turn around and offer them online courses that they can get free or nearly free. That business model simply does not work. There will be no such thing as a MOOC university.

Nelson believes that universities will end up effectively telling students: “Take the following online courses over the summer or over a certain period, and then, when you’re done, you will come to campus and that’s when our job will begin.” If Nelson is right, then universities in the future will spend much less time transmitting technical knowledge and much more time transmitting practical knowledge.

The goal should be to use technology to take a free-form seminar and turn it into a deliberate seminar (I’m borrowing Anders Ericsson’s definition of deliberate practice). Seminars could be recorded with video-cameras, and exchanges could be reviewed and analyzed to pick apart how a disagreement was handled and how a debate was conducted. Episodes in one seminar could be replayed for another. Students could be assessed, and their seminar skills could be tracked over time.

So far, most of the talk about online education has been on technology and lectures, but the important challenge is technology and seminars. So far, the discussion is mostly about technical knowledge, but the future of the universities is in practical knowledge.

And here are some gems from Thomas Friedman’s My Little (Global) School:

There was a time when middle-class parents in America could be — and were — content to know that their kids’ public schools were better than those in the next neighborhood over. As the world has shrunk, though, the next neighborhood over is now Shanghai or Helsinki … imagine, in a few years, that you could sign on to a Web site and see how your school compares with a similar school anywhere in the world.

Well, that day has come, thanks to a successful pilot project involving 105 U.S. schools recently completed by Schleicher’s team at the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, which coordinates the Program for International Student Assessment, or PISA test, and Jon Schnur’s team at America Achieves, which partnered with the O.E.C.D. Starting this fall, any high school in America will be able to benchmark itself against the world’s best schools, using a new tool that schools can register for at http://www.americaachieves.org. It is comparable to PISA and measures how well students can apply their mastery of reading, math and science to real world problems.

“If you look at all the data,” concluded Schnur, it’s clear that educational performance in the U.S. has not gone down. We’ve actually gotten a little better. The challenge is that changes in the world economy keep raising the bar for what our kids need to do to succeed. Our modest improvements are not keeping pace with this rising bar. Those who say we have failed are wrong. Those who say we are doing fine are wrong.” The truth is, America has world-beating K-12 schools. We just don’t have nearly enough.

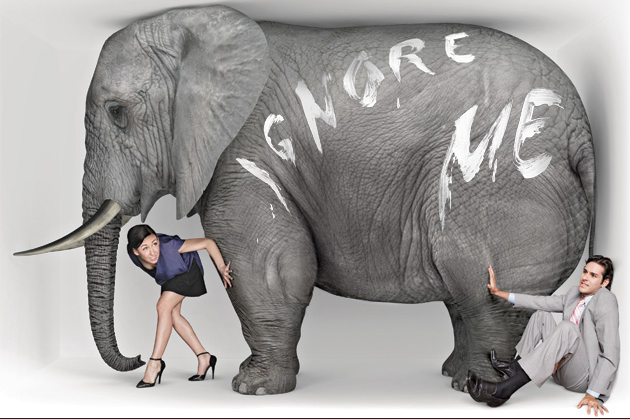

Seems like these and other recent pieces have created a proverbial tempest in a teapot. The arguments seem to rest on this idea: Testing and MOOCs are the spawn of Big Corporate America and have little to do with students learning or teacher’s teaching. Actually they are perceived as a threat to both. The underlying reasoning is the same for both. It boils down to the “facts” that testing and MOOCs reduce the person-to-person time, the opportunity for real discovery, lateral learning and whatever else is supposed to happen in the ideal classroom.

Here’s another quote from a piece I wrote last year that looks at the bigger picture:

Daphne Koller is a computer science professor at Stanford, and a MacArthur “Genius” Fellow. She has been working for years to make online education more engaging and interactive.

“On the long term, I think the potential for this to revolutionize education is just tremendous,” Koller says. “There are millions of people around the world that have access only to the poorest quality of education or sometimes nothing at all.”

Technology could change that by making it possible to teach classes with 100,000 students as easily and as cheaply as a class with just 100. And if you look around the world, demand for education in places like South Africa is enormous.

Almost two weeks ago, at the University of Johannesburg, more than 20 people were injured and one woman was killed trying register for a limited number of openings. Thousands had camped out overnight hoping to snag one of the few available places and when the gates opened, there was a stampede.

Koller hopes that in the future, technology will help prevent these kinds of tragedies.

The point is this is NOT an either-or situation. Technology and Corporations have always played a part in education from making pencils to printing books. The educational goal has always been to prepare students for success in higher education and/or the workplace. The focus is always on providing the best education possible. It just seems to get harder and harder to reach. If you don’t believe me, look at the numbers for high school graduation or grade school STEM test comparisons with other countries.

When we were a little country in a big world, making our own things, driving the global school bus, it was perhaps okay to only get a minimal high school education or even to leave classes behind and go to work. That no longer makes sense. As Thomas Friedman says this is now a global school and we compete with the best and brightest from around the world. As David Brooks says it not an either-or situation, but a chance to see how we can bring the technology and the teachers together to make education better.

So to the critics who try and place the conversation into a black&white and either-or context all I can say is “gray”. It’s all about change and change is messy. Change is also an opportunity. Education is not only technology led by greedy corporations, seeing privatizing and testing as opportunities for making lots of money. It’s not about Silicon Valley taking over the world mind with MOOCs that replace colleges and universities. It about trying to keep ahead of the wave that has already started to break over America and the rest of the world.

Should education be for free? Should we stop testing students to try and raise the overall standards of learning and preparedness? I have no final answers, only an interest in the ongoing conversation, and the forward motion that provides the best outcomes.