ADDIE Must Die!

NOTE (October, 2012): I first posted this piece in 2004. At the time I was looking at educational theories and methods that had been developed in the early 1970’s and that rather mysteriously became the de facto standard for developing educational programs.

I saw two major problems with ADDIE.

The first is obvious. The way we learned back then was simple and singular. Classroom, teacher, facing front in rows, be quiet, raise hands, take tests and more tests then PASS or FAIL. The ADDIE model worked and perhaps that is why is was adopted as THE standard even though there was no standards body that developed and accepted ADDIE. Thanks to Don Clark‘s research into ADDIE (which I recommend), it was developed by the US Army in 1975, and then copied by corporations, presumably by people who heard about it and experienced it in that environment. The problem is that today – and into the future if the past is any guide – we learn and will learn in dramatically different ways. Ways that ADDIE cannot support as a developmental model.

Second, either explicitly or implicitly ADDIE still is the default for defining, designing, developing, delivering, managing and measuring education. That means – and I still experience this – whenever educational programs are being created, the underlying thinking is A – D – D- I -E. This not only limits the way new educational programs are developed, it hamstrings the creative use of new learning technologies. Technologies that were not even dreamed of when ADDIE became the accepted guideline for development. It precludes many, if not all, of the powerful capabilities technology promises . Learning that is blended, mobile, flipped, social and more. So my conclusion then and now is that ADDIE must die.

The Premise

ADDIE is the illegitimate child of the Industrial Age, and using it is an addiction that almost always leads to formal training programs that are, in these digital days of rapidly advancing Blended,Mobile, Flipped and Social Learning, close to worthless if not actually counterproductive.

The good news? There is a better alternative …

Note: This is Part One of a two part series.

The future is a foreign country where

they do things differently than we do today…

Preface

I never minded school that much. It was the place where my friends hung-out and occasionally suffered through a class with me. I’m not sure what I learned or if it was of any use, but it was at least social. Learning in the workplace was the same until the computer started to pop-up everywhere. Then learning became lonely, it became anti-social.

Those of us who are trying t put the social back into the learning too often focus on the forest. The Big Enterprise 2.0 picture. This is a look at one of the trees – ADDIE – and it’s contribution to ongoing tradition of cranking out ineffective Enterprise 1.0 formal learning programs.

Change is Hard

Change is the most difficult yet desired state to which people want to move. Yet we live in the past in which habits rule and rules become habits. They don’t even need to be good habits or intelligent rules. Just habits and rules.

You’ve probably heard that expressions “If every problem is a nail, then every solution is a hammer”?

With ADDIE, if every problem is a lack of knowledge or know-how, then every solution is a formal training program …

Now I already know that you are falling into one of several categories of readers.

- You are so hooked on ADDIE that anyone who tries to show you that ADDIE has no clothes is an instant turnoff, and you are in the process of clicking away as fast as your finger can find your mouse

- You think ADDIE is okay, agnostic and can be used ‘back then’ as well as ‘moving forward’ and might consider reading what I have to say

- You develop really compelling and exciting social learning experiences and have no idea what ADDIE means … you can go.

Hopefully those of you in the first two groups will read on …

The ADDIE Habit

ADDIE. As you may (or may not) know, it stands for the five linear phases or guidelines for building effective training:

- Analysis

- Design

- Development

- Implementation,

- Evaluation.

ADDIE evolved into a more circular model in the late 1990’s and looked like this:

Evaluation became embedded in every part of the model. The variation was often called “Rapid Prototyping” which simply meant you ‘evaluated’ how well it was working at each A-D-D-I step.

There’s only one problem.

It no longer works.

Background Check

Here’s some ADDIE history. After doing an extensive search for the origin of ADDIE¹, I came to the conclusion that no one created the model. It was not the outcome of years of research, or a brilliant point of insight at the intersection of the disciplines that explore how we learn.

This idea is not new. It was, for example, originally published in an article by Michael Molenda of Indiana University, In Search of the Elusive ADDIE Model(Performance Improvement, May/June 2003).

During my halcyon ISD days, I didn’t really care who built the model, or that it was merely “… a colloquial term used to describe a systematic approach to instructional development, virtually synonymous with instructional systems development (ISD).”

Happy New Year 2005 (2013). Now I do.

When Learning Was a Noun

It was around the late 1970’s when ADDIE suddenly became the de facto standard for developing training programs for the US government and everyone else. ADDIE seems to have been adopted as an acronym in all the RFP’s that were issued by TWLA (Those Who Love Acronyms).

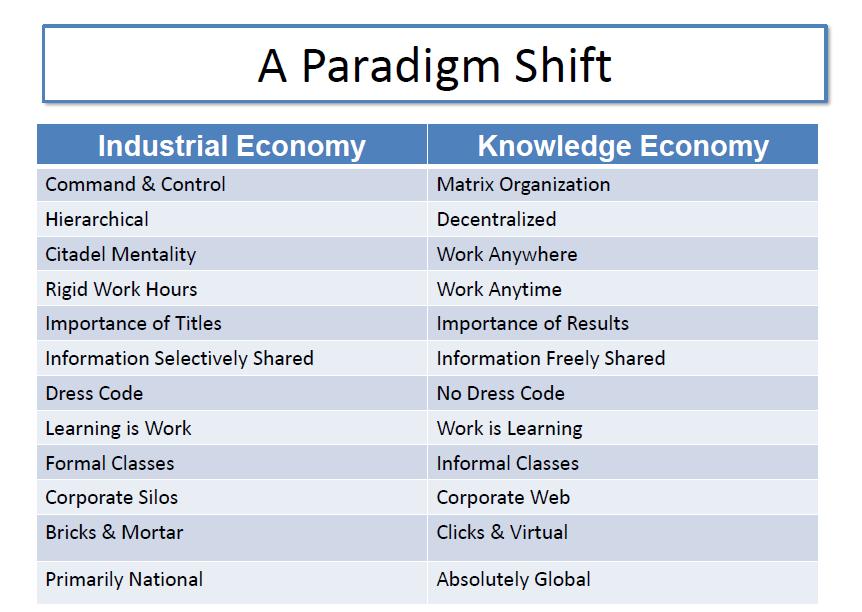

That meant that ADDIE had its roots in the Industrial Economy. A time when we managed hands and produced things. ADDIE was useful for helping people develop formal education programs in which knowledge was transferred and tests proved that it was ‘learned’.

ADDIE became the cutout you traced, the “paint by numbers” approach to developing and delivering programs that were the formal start – and too often the end – of your education. ADDIE was popular when organizations were bricks and mortar, development of programs was top down, and performance with regard to training was about getting a passing grade not adopting and adapting what you learned and transferring it back into the workplace.

When it came to really learning how to do anything, ADDIE led to the place where, if you were lucky, your informal education began. That was when you really started to learn how to do something².

Learning is Now a Verb

Times change. Take a look at the following chart to see how different the world of work is today:

Performance, Performance and Performance

Today it’s all about performance. What can you do for me? How can you do it faster and better? We’re well into the Knowledge Economy (aka Idea Economy), in which we manage minds and produce ideas. We no longer need to focus primarily on knowledge. We need to refocus on know-how and develop a model that supports learning how-to do something. Fix a thing. Make a thing. Come up with a solution. Steps to meet a challenge.

We need to focus on a developmental model that is more than just a “colloquial term”, one that helps incorporate new technologies and new ways of learning. One that enables rather than disables what we now understand as the learning process. A new model that provides knowledge AND is the launching pad for know-how and real learning in the future.

A model that drives a Social Leaning program.

From this perspective, let’s take a closer look at ADDIE and judge how relevant it is today. In Part Two of this blog, we’ll look at replacement model that enables Social Learning.

WARNING: Boring details and research up next!