By Anu Partanen

The Atlantic

The Scandinavian country is an education superpower because it values equality more than excellence.

Sergey Ivanov/Flickr

Everyone agrees the United States needs to improve its education system dramatically, but how? One of the hottest trends in education reform lately is looking at the stunning success of the West’s reigning education superpower, Finland. Trouble is, when it comes to the lessons that Finnish schools have to offer, most of the discussion seems to be missing the point.

The small Nordic country of Finland used to be known — if it was known for anything at all — as the home of Nokia, the mobile phone giant. But lately Finland has been attracting attention on global surveys of quality of life — Newsweek ranked it number one last year — and Finland’s national education system has been receiving particular praise, because in recent years Finnish students have been turning in some of the highest test scores in the world.

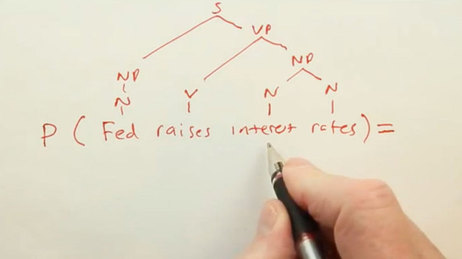

Finland’s schools owe their newfound fame primarily to one study: the PISA survey, conducted every three years by the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). The survey compares 15-year-olds in different countries in reading, math, and science. Finland has ranked at or near the top in all three competencies on every survey since 2000, neck and neck with superachievers such as South Korea and Singapore. In the most recent survey in 2009 Finland slipped slightly, with students in Shanghai, China, taking the best scores, but the Finns are still near the very top. Throughout the same period, the PISA performance of the United States has been middling, at best.

Compared with the stereotype of the East Asian model — long hours of exhaustive cramming and rote memorization — Finland’s success is especially intriguing because Finnish schools assign less homework and engage children in more creative play. All this has led to a continuous stream of foreign delegations making the pilgrimage to Finland to visit schools and talk with the nation’s education experts, and constant coverage in the worldwide media marveling at the Finnish miracle.

So there was considerable interest in a recent visit to the U.S. by one of the leading Finnish authorities on education reform, Pasi Sahlberg, director of the Finnish Ministry of Education’s Center for International Mobility and author of the new book Finnish Lessons: What Can the World Learn from Educational Change in Finland? Earlier this month, Sahlberg stopped by the Dwight School in New York City to speak with educators and students, and his visit received national media attention and generated much discussion.

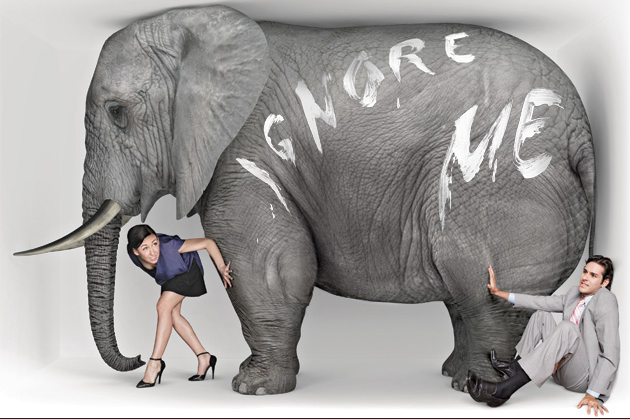

And yet it wasn’t clear that Sahlberg’s message was actually getting through. As Sahlberg put it to me later, there are certain things nobody in America really wants to talk about.

* * *

During the afternoon that Sahlberg spent at the Dwight School, a photographer from the New York Times jockeyed for position with Dan Rather’s TV crew as Sahlberg participated in a roundtable chat with students. The subsequent article in the Times about the event would focus on Finland as an “intriguing school-reform model.”

Yet one of the most significant things Sahlberg said passed practically unnoticed. “Oh,” he mentioned at one point, “and there are no private schools in Finland.”

This notion may seem difficult for an American to digest, but it’s true. Only a small number of independent schools exist in Finland, and even they are all publicly financed. None is allowed to charge tuition fees. There are no private universities, either. This means that practically every person in Finland attends public school, whether for pre-K or a Ph.D.

The irony of Sahlberg’s making this comment during a talk at the Dwight School seemed obvious. Like many of America’s best schools, Dwight is a private institution that costs high-school students upward of $35,000 a year to attend — not to mention that Dwight, in particular, is run for profit, an increasing trend in the U.S. Yet no one in the room commented on Sahlberg’s statement. I found this surprising. Sahlberg himself did not.

Sahlberg knows what Americans like to talk about when it comes to education, because he’s become their go-to guy in Finland. The son of two teachers, he grew up in a Finnish school. He taught mathematics and physics in a junior high school in Helsinki, worked his way through a variety of positions in the Finnish Ministry of Education, and spent years as an education expert at the OECD, the World Bank, and other international organizations.

Now, in addition to his other duties, Sahlberg hosts about a hundred visits a year by foreign educators, including many Americans, who want to know the secret of Finland’s success. Sahlberg’s new book is partly an attempt to help answer the questions he always gets asked.

From his point of view, Americans are consistently obsessed with certain questions: How can you keep track of students’ performance if you don’t test them constantly? How can you improve teaching if you have no accountability for bad teachers or merit pay for good teachers? How do you foster competition and engage the private sector? How do you provide school choice?

The answers Finland provides seem to run counter to just about everything America’s school reformers are trying to do.

For starters, Finland has no standardized tests. The only exception is what’s called the National Matriculation Exam, which everyone takes at the end of a voluntary upper-secondary school, roughly the equivalent of American high school.

Instead, the public school system’s teachers are trained to assess children in classrooms using independent tests they create themselves. All children receive a report card at the end of each semester, but these reports are based on individualized grading by each teacher. Periodically, the Ministry of Education tracks national progress by testing a few sample groups across a range of different schools.

As for accountability of teachers and administrators, Sahlberg shrugs. “There’s no word for accountability in Finnish,” he later told an audience at the Teachers College of Columbia University. “Accountability is something that is left when responsibility has been subtracted.”

For Sahlberg what matters is that in Finland all teachers and administrators are given prestige, decent pay, and a lot of responsibility. A master’s degree is required to enter the profession, and teacher training programs are among the most selective professional schools in the country. If a teacher is bad, it is the principal’s responsibility to notice and deal with it.

And while Americans love to talk about competition, Sahlberg points out that nothing makes Finns more uncomfortable. In his book Sahlberg quotes a line from Finnish writer named Samuli Paronen: “Real winners do not compete.” It’s hard to think of a more un-American idea, but when it comes to education, Finland’s success shows that the Finnish attitude might have merits. There are no lists of best schools or teachers in Finland. The main driver of education policy is not competition between teachers and between schools, but cooperation.

Finally, in Finland, school choice is noticeably not a priority, nor is engaging the private sector at all. Which brings us back to the silence after Sahlberg’s comment at the Dwight School that schools like Dwight don’t exist in Finland.

“Here in America,” Sahlberg said at the Teachers College, “parents can choose to take their kids to private schools. It’s the same idea of a marketplace that applies to, say, shops. Schools are a shop and parents can buy what ever they want. In Finland parents can also choose. But the options are all the same.”

Herein lay the real shocker. As Sahlberg continued, his core message emerged, whether or not anyone in his American audience heard it.

Decades ago, when the Finnish school system was badly in need of reform, the goal of the program that Finland instituted, resulting in so much success today, was never excellence. It was equity.

* * *

Since the 1980s, the main driver of Finnish education policy has been the idea that every child should have exactly the same opportunity to learn, regardless of family background, income, or geographic location. Education has been seen first and foremost not as a way to produce star performers, but as an instrument to even out social inequality.

In the Finnish view, as Sahlberg describes it, this means that schools should be healthy, safe environments for children. This starts with the basics. Finland offers all pupils free school meals, easy access to health care, psychological counseling, and individualized student guidance.

In fact, since academic excellence wasn’t a particular priority on the Finnish to-do list, when Finland’s students scored so high on the first PISA survey in 2001, many Finns thought the results must be a mistake. But subsequent PISA tests confirmed that Finland — unlike, say, very similar countries such as Norway — was producing academic excellence through its particular policy focus on equity.

That this point is almost always ignored or brushed aside in the U.S. seems especially poignant at the moment, after the financial crisis and Occupy Wall Street movement have brought the problems of inequality in America into such sharp focus. The chasm between those who can afford $35,000 in tuition per child per year — or even just the price of a house in a good public school district — and the other “99 percent” is painfully plain to see.

* * *

Pasi Sahlberg goes out of his way to emphasize that his book Finnish Lessons is not meant as a how-to guide for fixing the education systems of other countries. All countries are different, and as many Americans point out, Finland is a small nation with a much more homogeneous population than the United States.

Yet Sahlberg doesn’t think that questions of size or homogeneity should give Americans reason to dismiss the Finnish example. Finland is a relatively homogeneous country — as of 2010, just 4.6 percent of Finnish residents had been born in another country, compared with 12.7 percent in the United States. But the number of foreign-born residents in Finland doubled during the decade leading up to 2010, and the country didn’t lose its edge in education. Immigrants tended to concentrate in certain areas, causing some schools to become much more mixed than others, yet there has not been much change in the remarkable lack of variation between Finnish schools in the PISA surveys across the same period.

Samuel Abrams, a visiting scholar at Columbia University’s Teachers College, has addressed the effects of size and homogeneity on a nation’s education performance by comparing Finland with another Nordic country: Norway. Like Finland, Norway is small and not especially diverse overall, but unlike Finland it has taken an approach to education that is more American than Finnish. The result? Mediocre performance in the PISA survey. Educational policy, Abrams suggests, is probably more important to the success of a country’s school system than the nation’s size or ethnic makeup.

Indeed, Finland’s population of 5.4 million can be compared to many an American state — after all, most American education is managed at the state level. According to the Migration Policy Institute, a research organization in Washington, there were 18 states in the U.S. in 2010 with an identical or significantly smaller percentage of foreign-born residents than Finland.

What’s more, despite their many differences, Finland and the U.S. have an educational goal in common. When Finnish policymakers decided to reform the country’s education system in the 1970s, they did so because they realized that to be competitive, Finland couldn’t rely on manufacturing or its scant natural resources and instead had to invest in a knowledge-based economy.

With America’s manufacturing industries now in decline, the goal of educational policy in the U.S. — as articulated by most everyone from President Obama on down — is to preserve American competitiveness by doing the same thing. Finland’s experience suggests that to win at that game, a country has to prepare not just some of its population well, but all of its population well, for the new economy. To possess some of the best schools in the world might still not be good enough if there are children being left behind.

Is that an impossible goal? Sahlberg says that while his book isn’t meant to be a how-to manual, it is meant to be a “pamphlet of hope.”

“When President Kennedy was making his appeal for advancing American science and technology by putting a man on the moon by the end of the 1960’s, many said it couldn’t be done,” Sahlberg said during his visit to New York. “But he had a dream. Just like Martin Luther King a few years later had a dream. Those dreams came true. Finland’s dream was that we want to have a good public education for every child regardless of where they go to school or what kind of families they come from, and many even in Finland said it couldn’t be done.”

Clearly, many were wrong. It is possible to create equality. And perhaps even more important — as a challenge to the American way of thinking about education reform — Finland’s experience shows that it is possible to achieve excellence by focusing not on competition, but on cooperation, and not on choice, but on equity.

The problem facing education in America isn’t the ethnic diversity of the population but the economic inequality of society, and this is precisely the problem that Finnish education reform addressed. More equity at home might just be what America needs to be more competitive abroad.

More information

Professor Pasi Sahlberg’s website

“Finnish Lessons”, by Pasi Sahlbert

The OECD’s Better Life Index for Education

Nick Clegg speech on Social Mobility

Roy Hattersley’s New Statesman review of “The Spirit Level: Why More Equal Societies Almost Always Do Better” by Richard Wilkinson and Kate Pickett

Professor John Seddon addressing California Faculty Association

“Yes, we are all in this together”, New Statesman